So much has been written about

the Titanic that it must be difficult

for a writer interested in the subject to find a new angle. There are history

books a plenty, diaries and letter, transcripts of interviews, novels, poems

and plays, in addition to the myriad of TV series and blockbuster films. So it

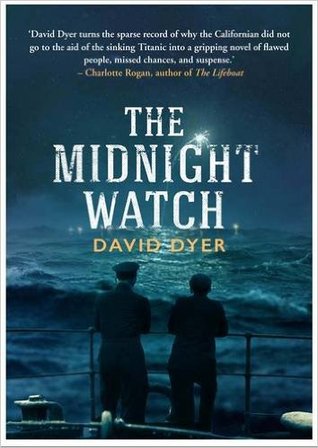

was a pleasant surprise to find that David Dyer has found something new to say

about the Titanic disaster in this,

his debut novel, ‘The Midnight Watch’.

So much has been written about

the Titanic that it must be difficult

for a writer interested in the subject to find a new angle. There are history

books a plenty, diaries and letter, transcripts of interviews, novels, poems

and plays, in addition to the myriad of TV series and blockbuster films. So it

was a pleasant surprise to find that David Dyer has found something new to say

about the Titanic disaster in this,

his debut novel, ‘The Midnight Watch’.

Instead of focusing on Titanic herself, Dyer turns his focus to

the men on board the Californian, the

ship that was closest to the Titanic

on the night of the disaster and saw her distress rockets but failed to go to

her aid. Specifically, he looks at how a series of decisions taken during one

cold April night impact the lives of three men: Stanley Lord, Captain of the Californian; Herbert Stone, her second

officer and John Steadman, a Boston newspaper reporter who soon senses blood

when the Californian docks.

By humanising the story and

narrowing the focus to these three men, Dyer cleverly avoids a pitfall of other

Titanic novels I have read – that of

having too large a canvas. The Titanic disaster

remains memorable for so many reasons: the luxurious nature of the ship, the

famous people on board who perished, the safety warnings ignored in the pursuit

of speed and luxury, the catastrophic loss of life amongst the passengers in

third class, the fact that it marked the beginning of the end of an era. All of

which is fascinating but is a quagmire for a novelist trying to capture it all.

Whilst Dyer touches on many of these key aspects, he keeps his focus firmly on

the Californian, bringing in other

aspects of the Titanic mythos only as

support for the story of Lord, Stone and Steadman. It is skilfully crafted and

results in a novel that is tightly plotted and fast paced without losing any

sense of the wider picture.

Lord, Stone and Steadman are all

rounded, fully-realised characters. The viewpoint switches between Steadman’s

first person narrative and a third person narrative, focusing on Stone. Steadman

is an excellent character to be inside the head of - passionate, dogged and

flawed and his hunt for the truth behind the Californian is the driving force of the novel. In contrast, Stone’s

sections are more reflective, showing a man in danger of losing his sense of

self and at odds with his place in the world. They are slower than Steadman’s

first person narrative but provide an important contrast and help to tease out

the finer details of the story. Lord, the most elusive of the three as he never

narrates the novel, could be seen as the villain of the piece – the Captain who

failed in his duty to aid a fellow vessel in distress – but Dyer treats him

with both respect and sympathy. The men of the Californian were not bad men, he is saying, but unfortunate. They

misinterpreted the signals given to them and, through a series of human errors

and fatal flaws, failed to go to Titanic’s

aid.

Without giving away any spoilers,

the latter part of the novel is a story within a story and finally takes the

reader onto the deck of the sinking liner herself. I rarely cry when reading

fiction but this final part bought a tear to my eye. Dyer has such an ability

to capture small details - the nervous tapping of fingers against teeth, the

flicker of a frown across a face, the delight a small child would have in

seeing an orange – and he brings this to the fore when describing Titanic’s sinking. The effect is very

moving.

All in all, I was surprised in

the extreme by this novel. It is an assured and, as far as I can tell, well-researched

book and genuinely adds a new perspective on a tale that has already been very

well told. For anyone interested in reading another perspective on the Titanic disaster, this is a suspenseful

novel of human flaws and missed chances that I would highly recommend.

My

thanks go to Atlantic Books and the Real Readers scheme for providing an

advanced copy of the book in return for an honest and unbiased review. ‘The Midnight Watch’ is published by Atlantic Books and is available in hardback now

from all good book retailers.

No comments:

Post a Comment